Two medical experts can view the same data and come away with different, even opposite, interpretations.

I know of one situation in which two specialists “read” a CT scan through radically different lenses.

The patient was coping with two active forms of cancer: bladder cancer and a kind of blood cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The CLL was considered stable (you can live with this kind of cancer for many years), and the patient was deemed a good candidate for surgery to address the bladder tumor.

When the urologist saw a CT scan showing enlarged lymph nodes, however, he got worried. If the bladder cancer had spread to the lymph nodes, or if the CLL was worsening, then he couldn’t recommend surgery.

A biopsy was ordered, which showed the lymph nodes were clear of bladder cancer. Then a CT scan to double-check those results.

The lymph nodes were still enlarged, so the patient returned to the biopsy table. When the second biopsy showed there was no detectable bladder cancer in the lymph nodes, the urologist still wasn’t convinced.

How could the CLL be stable, he reasoned, if the lymph nodes were growing?

Finally, the patient visited the hematologist to get his opinion on the various test results. The blood expert wasn’t concerned about the size or appearance of the lymph nodes at all, and he hadn't changed his mind about the CLL being under control.

“We don’t’usually order scans,” he explained. “We just look at the bloodwork.”

Same data, but two opposite conclusions-based on two contrasting ways of viewing the evidence.

As Thomas Kuhn showed back in the 1960s (in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions), we make deductions about the world we experience based on the models we hold in our mind.

Kuhn has been on my mind lately as I’ve been considering the different frameworks that shape our understanding of how the knowledge mobilization (KMb) process could or should work.

Those frameworks bear the stamp of mental models taken from the sciences and social sciences. As someone with a scholarly background in literary studies and decades of experience teaching technical and business communication, I find they're missing something.

At least on paper, popular KMb frameworks appear to overlook, or at least undervalue, the role that persuasive communication plays in transforming research into impact.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say that the current discourse of knowledge mobilization discounts communication.

The schematic diagrams representing KMb look comprehensive, but they leave out many different factors and subprocesses. Beneath the most comprehensive framework lies an invisible web of communication tasks and skills.

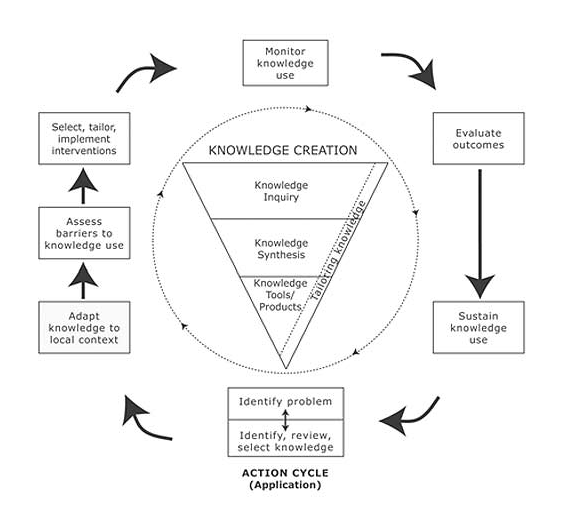

Take, for example, the popular Knowledge to Action Process Framework promoted by CIHR and adopted by many research organizations:

As detailed as it is, this schematic renders nearly invisible the intricate communication processes required to progress from one phase to the next.

Visually, it looks like knowledge flows seamlessly from inquiry through synthesis to knowledge tools and products. Yet to take knowledge from synthesis to tools and products involves many sub-steps.

The article that first presented the above framework does acknowledge that " knowledge producers can tailor their activities to the needs of potential users," but it seems to assume this will be a straightforward process. It identifies just five questions for knowledge producers to consider, starting with "What should be disseminated?"

From a communication perspective, however, questions of "what" emerge well into a process of in-depth inquiry that starts by focusing on the "who" and the "why."

Until you've thoroughly analyzed your target audience and the world they live in it's presumptive to identify the information they'll be ready to hear. What a knowledge producer may consider useful and educational will go ignored if it doesn't resonate with the knowledge user at a personal level.

A concrete example is the best way to illustrate the complex analysis required to "tailor [knowledge production] activities to the needs of potential users."

Imagine that you and I are working together on a research team, and our task is to take synthesized knowledge about how to prevent obesity in children and present it through an infographic. Before starting on this project, we’ve already had to go through the following steps:

- Identify the target audience(s)

- Analyze the target audience(s), considering both demographic and psychographic factors (beliefs, attitudes, and other psychological aspects)

- Engage the target audience to get their input

- Manage stakeholder input and expectations

- Choose the best medium (e.g., digital infographic on a website, poster, flyer, etc.)

These preliminary steps, hidden from view in the framework, are critical. They require strong skills in “rhetorical analysis,” the ability to consider all the different elements of a communication situation and make choices to maximize persuasion. For most research teams, this is where knowledge translation can easily go off the rails.

But let’s assume, we’ve thoroughly analyzed our audience and the possible ways to reach them, and we’ve decided an infographic is our best option. Now, we face another list of sub-steps, none of which appears in the framework:

- Identify the immediate persuasion goal for the infographic (what you want the audience to do after they’ve viewed the tool)

- Articulate core and supporting messages

- Craft an attention-grabbing headline

- Arrange the messages into a compelling storyline

- Create clear, simple data visualizations and conceptual diagrams to convey the meaning of the research findings

- Define the characteristics of a relatable, persuasive communication voice

- Write compelling text to unify the infographic and make it easy for the audience to accurately interpret data visualizations and conceptual diagrams

- Collaborate with a graphic designer or develop the infographic using graphic design software

- Write a compelling call to action

- Revise, edit, and proof the final product (ideally involving the target audience in the revision process)

Whew! And we haven’t even left the “knowledge creation” circle yet.

Once we get into the “action cycle,” we’ll need to repeat many of the steps listed above so that we can adapt knowledge to the local context and tailor interventions.

Within the action cycle, as we refine the infographic to make it more persuasive and helpful for our audience, we’ll also need to activate another set of communication skills, which could include:

- Stakeholder engagement

- Stakeholder management

- Leading from behind

- Presentation skills

- Negotiation skills

- Conflict management and resolution

- Needs assessment

- Emotional intelligence

Of course, the knowledge creation process and action cycle don’t exist in isolation from one another, and knowledge mobilizers often weave in and out of the two sections of the diagram. Consequently, any of the sub-steps and skills I’ve identified could be required at any point in the knowledge mobilization process.

The web of communication skills needed to move research through the frameworks representing the knowledge mobilization process is extensive and complex. And because it’s hidden, it’s easy to get tangled up in it, without understanding what’s happening.

How do you know your knowledge mobilization efforts are entangled in the complexities of persuasive communication? You probably feel stuck in some way. You might have trouble:

- Generating creative ideas for knowledge products

- Getting buy-in from key collaborators

- Feeling like you’re connecting emotionally with your target audience

- Expressing your ideas through language and visuals

- Making time to produce knowledge tools

If you’ve noticed any of these issues, then you’re not alone. And there’s a valid reason for your frustration.

Communication isn’t a mechanical process that can be captured neatly in a diagram. It’s a human process, which means it’s bound to be complicated and messy.

But here’s the good news: skills in persuasive communication are learnable. And when you start improving your communication abilities, you instantly start countering the sluggishness that plagues so many knowledge mobilization efforts.

Why do we accept that it takes a decade or more for research to move from the lab or library into practice? I think it has something to do with our undervaluing of the role communication skills play in speeding up the rate of knowledge mobilization.

Clear, compelling communication doesn’t equate with knowledge mobilization, which requires meaningful change, often at a system (or systems) level. But communication is the energy that activates knowledge mobilization frameworks, and through intentional skill-building, you can harness that energy to accelerate uptake and action among your audiences.

A shorter version of this blog post appeared in the Clarity Connect newsletter. To get other thought-provoking articles in your inbox, subscribe here.

1 Graham, I. et al. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26, 13-24.

Comments